Sydney, December 19: Don’t throw out your old clothing – researchers at UNSW Sydney have developed an effective process to turn old clothing and textiles into high-quality building products such as flat panels.

These high-end composite products can have a wood veneer look or a ceramic-style finish and were lab tested for qualities such as fire and water resistance, flexibility, acoustic and load-bearing capabilities but have not undergone any formal regulatory assessment.

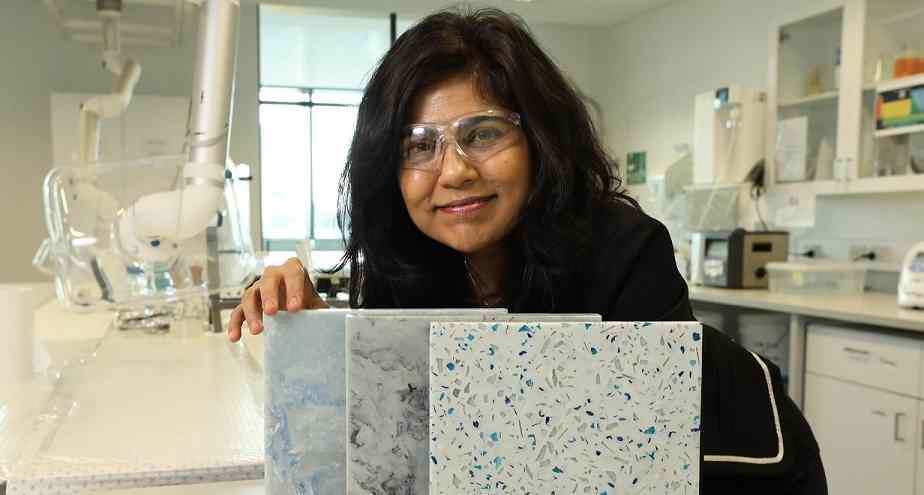

Researchers led by Professor Veena Sahajwalla, Director of UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT), have been scientifically reforming common waste items using prototype technology developed for a laboratory-scale ‘green microfactory’ to be launched in 2019.

The textiles materials tested exceptionally well in labs to mechanical performance properties including strength, flexibility and resistance. Further lab testing is required to explore and confirm these properties ahead of consideration of applying for any formal assessment against construction regulations.

Veena said green micro-factories can not only produce high performance materials and products, they eliminate the necessity of expensive machinery, save on the extraction from the environment of yet more natural materials and also reduce waste burden.

“These newly published results of the wonderful products developed from waste come as an effort to find ways to reduce waste and address our unsustainable landfill problems, which all countries are experiencing,” she said.

Questioning the fashion industry, Veena said that “consumers and the fashion industry have a lot to answer for, given that clothing is now one of the biggest consumer waste streams”.

The clothing and textiles industry is the second most polluting sector in the world, with 92 million tons estimated, to be thrown out a year, globally, accounting for 10% of the world’s total carbon emissions.

This follows a separate but related research exercise that converted used glass into high-quality ceramics suitable for benchtops and tiles in kitchens and bathrooms that can come in all sort of sizes, colours and finishes.

Reforming old clothing and mixed waste glass into various high-quality building products represents a new way to convert low-value waste into high-value products and materials.

This new research builds on an Australian National University (ANU) technology which can reuse same organic material for mobile-screens and processor, substantially reducing e-waste and making our mobile phones thinner, faster and actually bendable.

Veena said that when considering that the population growth trend is expected to jump from a current world population of 7.6 billion to 9.8 billion by 2050, the earth’s resources need to be preserved and re-used rather than put in landfill or incinerated.

“There is much that can be done right now given that scientifically-developed, proven methods are currently available through our green microfactory technology,” she said.

Rather than rubbish creating more landfill, Veena believes that green microfactory technology has the “potential to enable small and large-scale creation of newly manufactured products instead.”

Most people do not believe the waste materials they put out in their recycle bins is actually recycled but ends up in landfill, according to a recent consumer research. However, 91.7 per cent people surveyed, said that it is important for Australia to invest in technology to ‘reform’ most common waste to reduce landfill.

A major impediment to new solutions to the waste problem, Veena said, was getting the technology commercialised and into the market, and that required government incentives.

Vir Rajendra