Vaccine soon to be tested in Lymphoma patients

Stanford Univesity researchers are recruiting lymphoma patients to test a new cancer vaccine that had a 97 percent success rate in “curing” mice with cancer.

The clinical trial will involve about 15 patients with low-grade lymphoma and begin by the end of the year, according to a Stanford University news release.

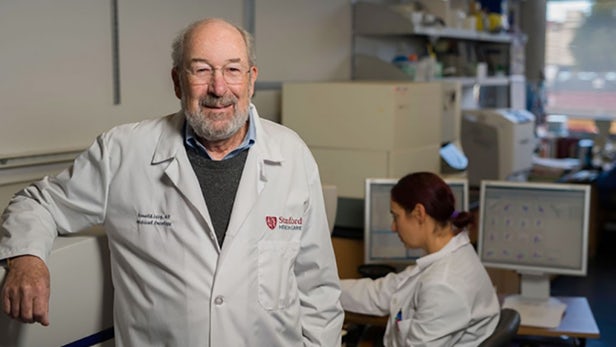

Lead researcher Dr. Ronald Levy, director of the lymphoma program at the Stanford Cancer Institute in California, said he believes the treatment could be useful for many tumor types.

If the new lymphoma-patient study proves that the vaccine is as successful in people as in mice, Levy said clinicians may one day inject the two agents of the shot into tumors prior to surgical removal of the cancer to eliminate it.

He added that the vaccine may also prevent recurrence of the cancer, due to the unidentified spread of lingering cancer cells, or even to head off the development of future tumors that arise due to genetic mutations like BRCA1 and 2.

“I don’t think there’s a limit to the type of tumor we could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system,” Levy said.

The work is an example of Stanford’s focus on precision health, which aims to anticipate and prevent disease in the healthy and precisely diagnose and treat disease in the ill.

In January, Levy’s research team reported that a new study found the two-compound vaccine stimulated the immune system in mice after being injected directly into tumors and killed those cancer cells.

The shot also destroyed rogue cells from the tumors that had already traveled to other sites in the rodents’ bodies. Levy added that the approach worked for lymphoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, and the deadly skin cancer melanoma.

In reporting those findings, in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Levy said he has no reason to believe it wouldn’t also work in people. Because the treatment is injected directly into the tumor in very small doses, side effects would likely be minimal, he added.

Immunotherapy is a way of swinging the odds back in the immune system’s favor. Some of the common approaches include targeting the built-in switches that stop natural cancer-fighting proteins do their thing, boosting other proteins that ramp up the presence of cancer-fighting T cells, and removing T cells, genetically engineering them to attack tumor cells, and then returning them to the body.

He explained that cancer cells trigger immune system T-cells to attack and destroy the tumors. But as cancer grows, tumors develop ways to suppress the activity of the T-cells, allowing them to multiply, grow, and spread to other parts of the body.

The two agents used in the experimental vaccine boost the immune system to counteract the evasive maneuvers of tumor cells.

So far, the researchers were able to eliminate four types of cancer in mice. If the new clinical trial is successful, Levy suggested the treatment would likely be combined with other therapies (such as surgery and radiation) to overwhelm the disease.